“In the beginning, it was just chasing the sounds and finding new sounds.” This is how Christina Kubisch describes her first forays into an ongoing project known as the Electrical Walks: experiential, semi-guided sound tours the artist has created in cities around the world, from Berlin to Riga, New York to Mexico City, Hong Kong to Athens and Reykjavik, and more than 70 other locales. But rather than listening to the ambient noises of urban life, Kubisch dials in on the frequencies that normally evade detection. These walks rely on specially built headphones, designed by the artist in collaboration with engineers, that register electromagnetic signals from the environment and convert them into audible sound.

A pioneering German sound artist and composer, Kubisch (b. 1948) studied painting, composition, and electronic music and trained as a professional flautist. In her early career she intersected with such pivotal figures in the world of experimental music as John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, and Annea Lockwood, but by the 1970s she was primarily focused on incorporating different forms of sound technology to create experiential and often participatory forms of art, working with performance, sound installation, electromagnetic induction, and ultraviolet light.

The Electrical Walks grew out of early pieces she constructed using induction cables. In the early 1990s, while Kubisch was in San Sebastian, Spain, to install a large cable installation, she walked through the gallery and suddenly heard many other sounds—sounds that were not ones she had devised for the piece. She was distraught and assumed the interference was due to a technical failure. But then, the epiphany: On the other side of the wall was a post office, and she came to realize that the electromagnetic frequencies from the computers there were transmitting through the walls and being channeled by her cables. It was at that moment that Kubisch realized: “I’m no longer alone with my installations.”

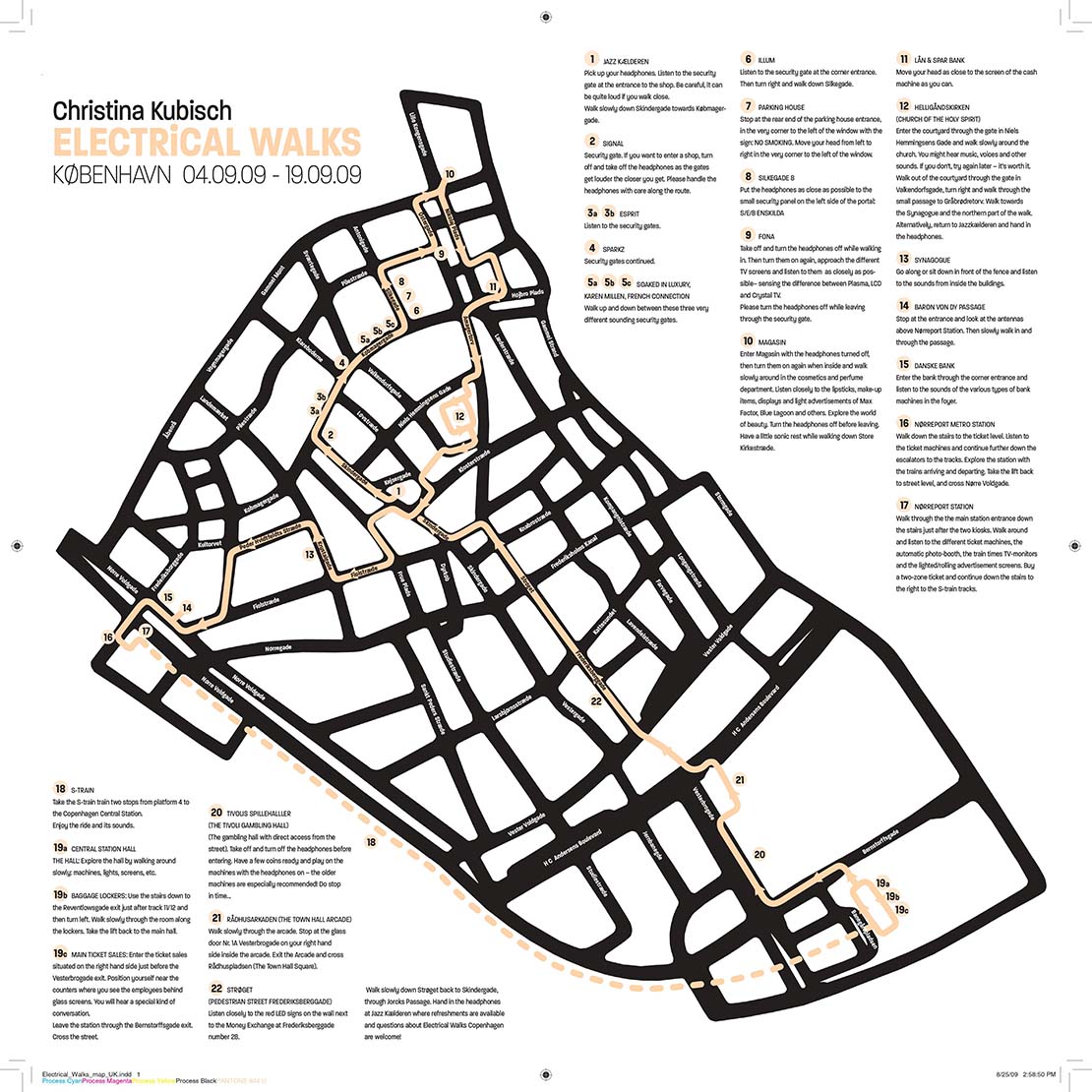

The first official Electrical Walk was held in Cologne in 2004. When she is devising a new walk, the artist maps a given section of the city, particularly noting electromagnetic hot spots like ATM machines, security systems, or public transit where signals are particularly noticeable or distinctive. Some sounds are more or less the same everywhere, but the artist notes that different regions often have a similar soundscape: For example, the sounds found across cities in Asia, or throughout Eastern Europe, are more similar to one another than to cities in Western Europe. Quite often public transit systems—such as a bus, or even the difference between an electronically run subway system as opposed to one operated by a driver—provide some of the most distinctive source material. Kubisch now observes that in the early aughts, much of the machinery in use was still analog. As a result, the sounds she discovered using her headphones were often more musical and rhythmic. Digital sounds, which proliferate now, tend to be based on higher frequencies and have a different timbre.

The first official Electrical Walk was held in Cologne in 2004. When she is devising a new walk, the artist maps a given section of the city, particularly noting electromagnetic hot spots like ATM machines, security systems, or public transit where signals are particularly noticeable or distinctive. Some sounds are more or less the same everywhere, but the artist notes that different regions often have a similar soundscape: For example, the sounds found across cities in Asia, or throughout Eastern Europe, are more similar to one another than to cities in Western Europe. Quite often public transit systems—such as a bus, or even the difference between an electronically run subway system as opposed to one operated by a driver—provide some of the most distinctive source material. Kubisch now observes that in the early aughts, much of the machinery in use was still analog. As a result, the sounds she discovered using her headphones were often more musical and rhythmic. Digital sounds, which proliferate now, tend to be based on higher frequencies and have a different timbre.

Kubisch sees the Electrical Walks as opening up a portrait of a city to its inhabitants. Through the guided use of technology and the formative individual and group encounters, participants are immersed in new areas, environments, and material (if unseen) realities of a place that they otherwise feel they know intimately. Reflecting on her childhood in the years immediately following the Second World War, Kubisch recalls playing in the urban ruins and inventing games centered around finding treasure that she and her playmates believed was hidden beneath the rubble that surrounded them. In a way, the Electrical Walks achieve a similar act of revealing multiple worlds running alongside one another. Sometimes we just “need someone who opens up these worlds for us,” Kubisch muses. Someone who helps open up “these other possibilities.”

The following is an excerpt from “‘The Sound Can Touch You Directly’: Christina Kubisch on Electronic Sound Art,” interview with Caitlin Woolsey for In the Foreground: Conversations on Art & Writing, a podcast from the Research and Academic Program at the Clark Art Institute. Interview recorded November 23, 2020.

Christina Kubisch: From the beginning, what I tried was to make a portrait of each city. And actually, the electromagnetic portrait of a city is in a way very close to other [kinds of] portraits of the city, like if you would do acoustic field recordings, or if you would make a social study. The electromagnetic world reflects what is going on in the city: Where the places with a lot of money and banks are; where the shopping areas are; where residential areas with very small electromagnetic fields are [located]; where are the strange sounds coming from? …. Every city is different. And besides the global [machines that are the same everywhere], sounds like the security safety entrances at the shops, you always find something which is only in that city, which is really typical for that city. But [the process] has changed in the sense that some years ago, I started to make guided walks. Before, I just had a map. The map was my score, and [it was] a score for [other participants] … who would go out themselves. Later on, I thought it would be nice again to be with people to go around. So, for example, in New York two years ago [in 2018], during the festival Time:Spans, I had two Electrical Walks lasting one hour and a half. … The public I [encountered] was so different every day … from housewives who had never [experienced] anything like it, to specialists and musicians. They were all together. And they all started to talk. So, this is something I like very much, and which nowadays is very much part of the [Electrical Walks] as works, as guided walks.

But still for every Electrical Walk, I [create a] map version. What is important is that there are places people know, but which may be places they never go. When I go to a new city, I’m very naive. I don't know anything, so I can go to places where [locals] would never go because they think it’s not interesting. I can just go to a courtyard or walk around the corner, or go to a place they think is very boring, and I find something interesting. It lets them know the city from a view they would not have normally.

Caitlin Woolsey: Is that how you start, when you’re developing a new sound walk in a new city? That you go on your own explorations and just listen?

Kubisch: In the beginning, I just follow the sounds. That’s the nicest day. The first day is always the easiest day, because I just walk around. From time to time, of course, I have to rest my ears because it’s very tiring. And I make notes. I always have a map of the part of the city where the work will take place. The difficulty is that it’s always a circular walk because people have to get their headphones and then bring them back. And so sometimes in this area I will have places that are not as interesting, but [the participants] have to go through to come back, or to get somewhere. So, there are many possibilities. In the beginning I find so many sounds. Then in the end, I have to really limit them, and make a kind of choice, and kill my favorite electromagnetic babies and so on. It’s very hard. But if it’s a good walk, I feel it’s a kind of continuity. This takes at least another two days [to finalize the route], and then there has to be the text [that accompanies the walk].

When I’m ready, I always ask one of the organizers …. to go with me to get feedback. Sometimes they say it’s too long, or say ‘do a little bit more here.’ I’m so used to the sounds sometimes that I’m a little bit too quick, or I have too many things [included]. But since they [are] listen[ing] to it for the first time, they need more space and more time. All this is always good [as part of the creative] experience [for me to get] feedback from other people. This part is quite important to me because the normal thing is to go to a concert and to sit there, and you have your beautiful or whatever experience, and clap hands, and then maybe afterwards you have a glass of wine or you talk to your friends, but that’s it. But here, it’s … people who [have] never met [before], who are coming from different backgrounds to do something they [haven’t done] before. In the beginning, sometimes, they’re even a little bit afraid, because I bring them, for example, into places and they know they look a little bit strange with the big headphones on, and they know they behave in a strange way, they know other people are looking at them. But after 10 minutes, they forget. If it’s a good group it’s really fun, because they start to go everywhere and make experiments and they move. … I like this group experience.

Woolsey: Do you think about potential political or social dimensions of your work? How the walks bring people perhaps into neighborhoods or into parts of the city that they wouldn’t normally go because they wouldn’t feel comfortable, or it wouldn't feel like a place that would be open to them?

Kubisch: There are several things [at play]. To participate [in an Electrical Walk], you behave as you would not behave normally. If you go into a shop and you [wander] very closely along a cosmetic counter, for example, the creams and the lipsticks, and you listen to them, you don’t look at them … someone very often will come [up and] say, ‘What are you doing?’ You can give them the headphones and say, ‘Listen. It sounds interesting,’ or ‘It sounds terrible,’ or whatever. But you see very often that people will get suspicious because you don't behave the way you are expected to behave. This is, for me, always an interesting experience. Sometimes [people will] even say, ‘Don’t enter the shop again.’ When we had a group in Spain, we had the police [called on us]. So, things like that happen too, but not very often, fortunately.

Then, of course, there is the discovery of this magnetic world by itself. All this is around us and we had no idea before. And the question that comes up all the time is: What does it do to us? Is it good or bad for our bodies? And these discussions are very important, and they arise almost every time after any Electrical Walk. And it’s also discovering that what you see is not a very secure thing. I mean, you may look at something––and the sound is so different. You look at a park, and you hear a heavy beat. Listening, you now know there is something maybe under the earth.

I think the Electrical Walks make you feel a little bit unsafe. They take you out of your normal perception. And if you consider this a part of politics, then I would say, yes—the work is political as well.

Caitlin Woolsey is an art historian and poet who specializes in the historical confluence of visual art, performance, and media. She is the assistant director of the Research and Academic Program at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, and lecturer in the Williams Graduate Program in the History of Art. She is at work on a book exploring the intersections of sound technology, experimental poetry, and expanded collage practices in the decades following World War II.

TOP: Christina Kubisch engaging in an Electrical Walk in Oslo, Norway, May 2019. Photo: Frank Paul. © Christina Kubisch.

MIDDLE: Electrical Walk in Shanghai, China, November 2018. Photo: Jan Prokopius. © Christina Kubisch.

BOTTOM: Map of an Electrical Walk in Copenhagen, Denmark, September 4–19, 2009. © Christina Kubisch.